When environmental dominoes fall, it’s called a “cascading event”. The effect on one species, for example through over-fishing, loss of habitat, or reduced food supply, flows onto other species, both above and below it in the food chain.

This seems to be happening in Tasmania with the arrival of long-spined sea urchins in 2012. It appears octopus numbers are increasing, thus reducing lobster populations. Lobsters are a major predator of sea urchins. Without lobsters, sea urchins are devasting the kelp forests, which are an important habitat for lobsters. All this because a northern species has established itself in the formerly too-cold southern waters.

The long-spined sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii), a native of New South Wales, [also found in Victoria] was first recorded in 1978 in Tasmanian coastal waters. From an epicentre near St Helens on the east coast, it has since steadily spread southwards, and is now being found in Macquarie Harbour in the west of Tasmania. It is an invasive warm-water species, and is thought that the East Australian Current introduced the larvae naturally to Tasmania thirty or so years ago.

It has become an important marine pest there, along with the (non-native) northern Pacific sea star.

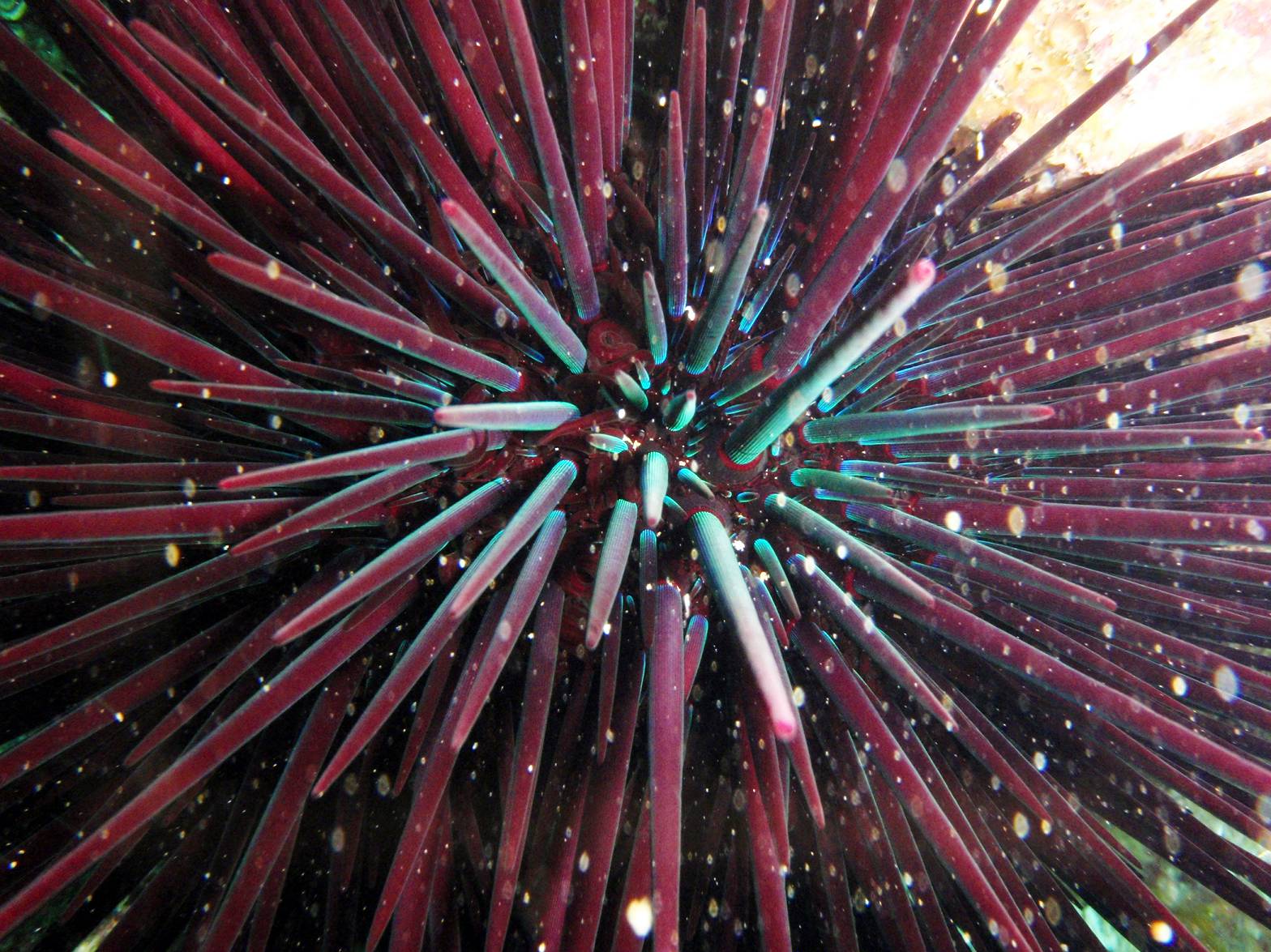

Also known as spiny sea urchins, Roger’s sea urchins, black (or purple) sea urchins, long-spined sea urchins can grow to 10 -17 cm. They are different to most species of sea urchins as their spines are hollow, and these are rough to touch from the tip to the base.

The spines, up to 8 cm in length, are dark purple/almost black but can, in strong sunlight, appear to have a green iridescence. The body (test) varies in colour. In Victoria, the bare test has been described as whitish with light mauve tubercules, whilst in NSW and Tasmania it is recorded as ranging from deep red to black.

It is the largest sea urchin in Tasmania, and is a major marine pest as it aggressively overgrazes seaweed and other marine organisms –you might see the extensive ‘barrens’ or ‘white rock’ they produce. This in turn harms the entire marine ecology, including the commercially important species such as rock lobster and abalone. In fact, abalone appears to become more active when the sea urchin is present, moving into what is called ‘cryptic habitats’ – trying to move or ‘run away’ or ‘hide from’ the sea urchins.

But, good news is that Tasmania is dealing with this destructive and voracious marine vermin in a novel, yet lucrative way. By harvesting, processing and exporting the roe of the long-spined sea urchin to Japan, a Tasmania is turning a pest into a profit. Read more about it in Tasmania here.

It is called “uni” in Japan (pronounced oo-ni) and used mainly in sushi and sashimi. It is considered to be an exquisite (and expensive!) delicacy. Apparently it tastes like creamy caviar.

Photos: David Parsons, St Helens, Tasmania